From sumptuous engravings to stick-figure sketches, Passover Haggadahs − and their art − have been evolving for centuries

Published in News & Features

The Jewish festival of Passover recalls the biblical story of the Israelites enslaved by Egypt and their miraculous escape. During a ritual feast known as a Seder, families celebrate this ancient story of deliverance, with each new generation reminded to never take freedom for granted.

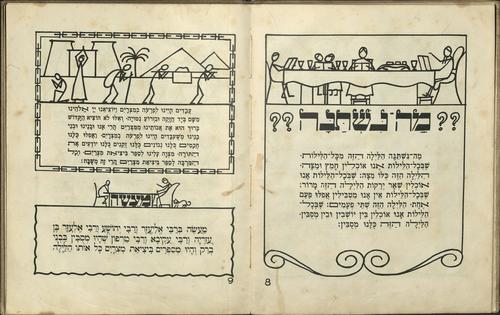

Every year, a written guide known as a “Haggadah” is read at the Seder table. The core text comprises a description of ritual foods, the story of the Exodus, blessings, commentaries, hymns and songs. The word Haggadah – “telling,” in Hebrew – was derived from Exodus 13:8, a verse which instructed the Israelites to commemorate their liberation and tell the story to their children.

Even though the ancient festival that became Passover has been celebrated since the biblical period, the complete text of the Haggadah emerged only in the eight to ninth centuries. And it was not until the 14th century that fully developed, sumptuously illuminated versions emerged, used by the Jewish communities of Germany, Italy and Spain. Medieval editors integrated decorative borders, such as fantastical, beastlike creatures borrowed from the wider culture.

This artistic license, together with slight modifications to the text over time, meant that the Haggadah became both a mirror and a commentary on the societies in which they were produced. Here at the University of Florida’s Price Library of Judaica, where I am curator and a medieval Hebrew scholar, we have hundreds of Haggadahs – each one a window into how Jews in a particular time and place adapted the telling of the Passover story.

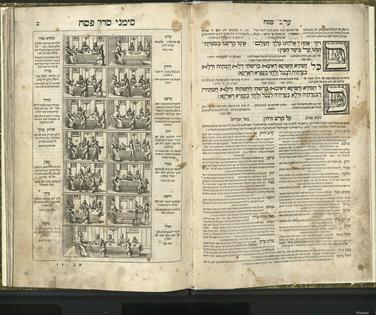

One of the greatest examples our library has of this blending of cultures was printed in Amsterdam in 1695.

The Amsterdam Haggadah was illustrated by Abraham Bar Yaakov, a German pastor who converted to Judaism. Abandoning the standard use of woodcut images, Bar Yaakov created a series of copper engravings based on Bible illustrations by the Swiss engraver Matthäus Merian the Elder. In addition, he incorporated a pull-out map of the route of the Exodus and an imaginative rendering of the Temple in Jerusalem.

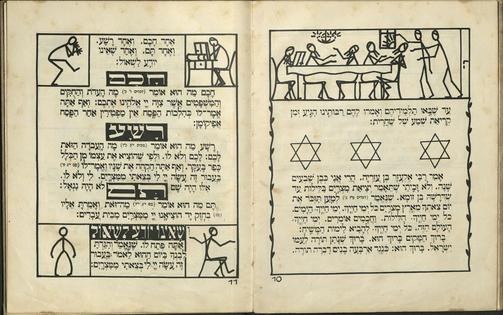

Bar Yaakov also added an image of the “four sons” standing together – one of the many elements of Haggadahs designed to engage and instruct children sitting through the long Seder meal. Each son represents a different type of child, described by their attitude toward Passover: wise, wicked, silent and one who does not even know how to ask questions about the holiday.

In medieval Haggadahs, the wicked son was usually portrayed as a combatant – the personification of evil for European Jews who had suffered recurrent mob raids and violent expulsions. In Bar Yaakov’s rendering, the wicked son is a Roman soldier precariously balanced on one foot and looking back toward the wise son, who is depicted as Hannibal, the Carthaginian general who battled Rome in the third century B.C.E.

The second edition of this Haggadah was printed with additional engravings in 1712 by Solomon Proops, founder of an acclaimed Dutch Jewish printing house. The text, traditionally written in Hebrew and Aramaic, included instructions in Yiddish and Ladino, the everyday languages for Jews in Europe. The Ladino translations were specifically geared toward Sephardi Jews who arrived in the Netherlands after being expelled from Spain and Portugal, as well as Portuguese “Conversos” returning to Judaism after their ancestors had been forced to convert to Catholicism.

The Amsterdam Haggadah proved to be incredibly influential on later versions, with its illustrations copied into the modern era.

...continued

Comments